Artists impression of how St Mary Spital may have appeared before the Dissolution. Museum of London. Artist Faith Vardy.

St. Mary Spital Augustinian Priory and Hospital covered the area known today as Spital Square. Standing outside the city walls it was bordered from the west by Bishopsgate Street where entrance was via the Great Gate and to the north where Folgate Street now stands. Stand today in the square and you will feel swallowed up by the high rise modern buildings constructed from stark unforgiving steel and glass and yet the ground plan of the Priory still survives today if you look carefully enough.

The site of the Priory and hospital of St Mary Spital – Agas Map c.1560-70. The main entrance would have been from Bishopsgate Street via the Great Gate. This Gate may have stood at where today’s Spital Square joins Bishopsgate Street and opposite the road then known as Hog Lane, now known as Primrose Street, the beginning of which can be seen on this section of the map…see red circle.The line of trees at the top of the map represents a lane that later evolved into Folgate Street. Although the Priory and Hospital had been swept away when this map was made its ghost remains traceable in modern day Bishopsgate/Spitalfields.

Bishopsgate and Spital Square today. Primrose Street and Spital Square Road opposite each other merge into Bishopsgate. At the top you can see where the line of trees from the Agas map had developed into Folgate Street. Amazingly Elder Garden, circled in red, still survives in the same area and oblong shape as the one in the Agas map. The artillery area covered where the church, cloister and canons refectory/dining room stood. The shape of the artillery area is still discernible in what is now Spitalfields market, bottom of map.

The precise position of the Great Gate has not been proven conclusively but there is reason to believe that it was where Spitalfield Square Road opens up and opposite Primrose Street. The highly detailed Copperplate map shows, at that position, a long roof which could have been the remains of the Gate House.

The Copperplate map c.1557. Middle left – the road now known as Primrose Street merges into Bishopsgate opposite what could be the Great Gate House standing at what is now the beginning of Spital Square Road.

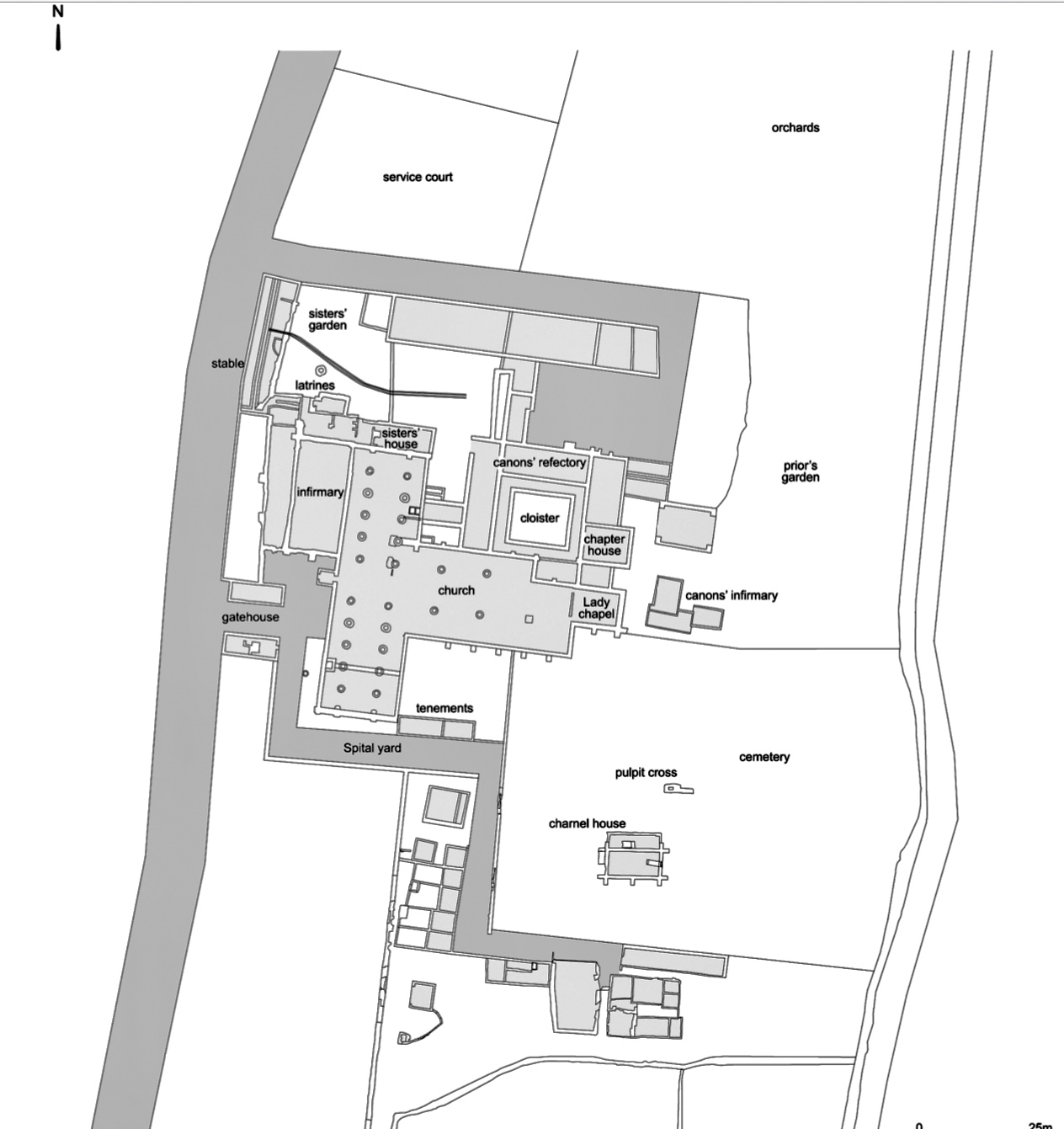

Plan of St Mary Spital. With thanks to researchgate.net

St Mary Spital founded in 1197 by Walter Brunus, a wealthy merchant and citizen of London, and his wife Roisia, stood on the east side of Bishopsgate Street on land where once stood a Roman cemetery. Originally known as the Priory of the Blessed Virgin Mary without Bishopsgate, sometimes known as the New Hospital of St Mary without Bishopsgate, later shortened St Mary Spital. By the way – the Latin word “hospitali” had mutated variously into Spital, Spital House, Spittal or even ‘Spytell’. Sir Robert Gresham, Lord Mayor, in his letter to Thomas Cromwell , August 1538 mentioned :

“Nere and within the citie of London be iij hospitalls or spytells, commonly called Seynt Maryes Spytell, Seynt Bartholomewes Spytell and Seynt Thomas Spytell, and the new abby of Tower Hyll, founded of good devocion by auncient ffaders, and endowed with great possessions and rents onley for the releffe, comfort, and helyng of the poore and impotent people not beyng able to help themselffes, and not to the mayntennance of chanins, preestes, and monks to lyve in pleasure, nothyng regardyng the miserable people liying in every strete, offendyng every clene person passyng by the way with theyre fylthy and nasty savours.”

Gresham was attempting to get a stay of execution for St Mary Spital. He failed.

It was founded with the intention of tending to ailing and weary pilgrims, the sick, especially the poorer ones, people who had been injured and maimed in accidents and caring for pregnant women until their delivery, as well as looking after the children of the women who died there in childbirth, until they attained the age of seven (1). However it should be remembered it would not have been a hospital as we know it today, obviously, think church with beds in the aisles although St Mary’s also had a separate two story infirmary built on the west side of the church in c 1320–50. Possibly this smaller building may have been utilised for higher status patients. It’s well-documented that royal servants, such as a servant of Edward’s I’s confessor, two of Edward III’s yeomen, a Robert de la Naperie maimed in the king’s service, as well as wealthy benefactors of the priory and infirmary such as John de Tany who died there in December 1315, were also cared for there as well poorer people. As well as tending to the sick the focus would have been on prayers and the spiritual side of things.

However not all went to plan all of the time. A hiccup occurred in 1303 when during a visit by the Archbishop of Canterbury it was revealed that lamps were no longer being lit between the patients beds as well as the sisters had not received their allowance of food, money or clothes. The Archbishop ordered that the lamps should be returned and maintained for the ‘comfort’ of the sick with immediate effect. That was not all for the canons also managed to get themselves reprimanded for disobedience – ‘for frequenting the houses of Alice la Faleyse and Matilda wife of Thomas’ . Interestingly the houses where these ladies lived were within the precincts of the hospital. Hmmmmm – what Thomas made of it who knows – naughty, naughty canons. However all good things come to an end and I’ll let Professor William Ayliffe of Gresham College take up the story here –

‘The Bishop of London then dismissed the prior and he appointed the sub-prior of St Bartholomew’s. The reason they did that was that everybody trusted St Bartholomew’s. They trusted it right the way through history. Henry VIII trusted St Bartholomew’s, and in fact, he endowed some money to it. The deposed prior, however, was not just sacked; he was treated rather like the head of some corporation in the City of London today. He was given a room near the infirmary, a double allowance of bread, ale and fuel, forty shillings a year, and an allowance for his servant, who was given the astonishing amount of a gallon of beer, a loaf of black bread and a dish from the kitchen a day, and he also had a companion assigned to him. This is really living it very well by medieval standards (2)’

The infirmary was to become the largest in medieval London, although St Leonard’s in York pipped it with just over 200 beds, and was run by twelve lay brothers and lay sisters under the supervision of a prior. At the time of closure there was a total of 180 beds with two patients in each. A list of parish churches and monasteries in London of about the mid-fifteenth century mentions ~

’Seynt Marye Spetylle. A poore pryery, and a parysche chyrche in the same. And that pryory kepythe ospytalyte for pore men. And sum susters yn the same place to kepe the beddys for pore men that come to that place’

The Wyngaerde map c.1543-1550. By the time the map was drawn up much of the Priory had been swept away.

However at the time of its dissolution in 1539 the fabric of the church was apparently already in disrepair, as in August 1538, Sir Richard Gresham, reported to Thomas Cromwell that on the previous Wednesday afternoon ’the Rouffe and the Leedes and allssoo the Roodeloffte’ of the church had fallen down’ . It’s possible the infirmary was in better condition because although twenty-five tons of lead had been received by James Needham, surveyor of the King’s manors, from the demolition of the Priory for the repair of ’Westminster hall Rouff‘ by July 1540, the sick were still occupying the hospital in December 1540, a lease granting them the right to there lie for term of their lives (3). However despite this slight respite for the patients, the Priory and hospital were utterly swept away – the precincts to become an artillery ground – with such thoroughness that nothing remains today except for the remains of a charnel house. This charnel house was situated on the east side of the church in the cemetery and was discovered during major excavations carried out by Museum of London Archaeology in 1999-2002. The upper floor of the charnel house had been used as a cemetery chapel in the early 14th century. Nothing remained of the chapel but following the excavation the charnel house was preserved in situ and today can be viewed from behind glass below pavement level in Bishops Square.

The cemetery had been in use for over 400 years until the Priory and its precincts were demolished in 1540. During the London Museum excavations many single graves were found but also many multi layered burial pits. These pits were thought to contain the victims of catastrophic events of high mortality such as plague. There is also reason to believe that some of the remains in the pits were victims of famine which was not a stranger to Medieval London. However all of the remains had clearly been buried with an obvious high level of care and reverence and not merely tumbled in as was the case with some plague pits. The majority of bodies were aligned with heads to the west and feet facing east and in some cases children were placed at the foot end of the grave, laid out north-south, apparently to make optimum use of the space within. More information about this can be found here.

One of the multi burials. Clearly even in times of catastrophic and overwhelming events such as plague and famine, the canons ensured the people in their care were buried with prayers, reverence and kindness.

Over 10,500 skeletons would be discovered of which 3000 were from the 13th century. These large numbers of deaths have now been linked to a famine that is now thought to have been linked to a ‘devastating’ vulcano eruption in Indonesia. This eruption may well have caused far flung climate change which led to crop failures worldwide (5).

Following on from the Dissolution of the Monasteries the land that was not turned into the Artilliary practice ground was either given to those in royal favour or sold for the rich to build large residences upon. In the late 17/18th centuries streets of beautiful houses such as Folgate Street were built which remained until the 1920s when most of them, in their turn, were razed to the ground – this time for the enlarging of the old Spitalfields market. Such is progress. Spital Square and its environs are now vibrant areas with people in droves using the eateries, shops and offices therein. Not many of them as they go about their busy day to day lives realise that beneath the ground they walk on once stood the busiest Medieval Hospital in London, that took in the poorest, raised the babies of the mothers who died there in childbirth and provided a refuge and succour for medieval Londoners for almost 400 years.

- BHO p21-23 Survey of London: Volume 27, Spitalfields and Mile End New Town

- William Ayliffe ST BARTHOLOMEW’S HOSPITAL AND THE ORIGIN OF LONDON HOSPITALS

- The London Encyclopaedia p.763. Edited by Ben Weinberg and Christopher Hibbert.

- BHO p21-23 Survey of London: Volume 27, Spitalfields and Mile End New Town

- A bioarchaeological study of medieval burials on the site of St Mary Spital: excavations at Spitalfields Market, London E1, 1991–2007

If you liked this post you might be interested in

The Abbey of the Minoresses of St Clare without Aldgate and the Ladies of the Minories

THE ANCIENT GATES OF OLD LONDON

Murder and mayhem in medieval London

2 thoughts on “THE MEDIEVAL PRIORY AND HOSPITAL OF ST MARY SPITAL”